The format war that Beta has won

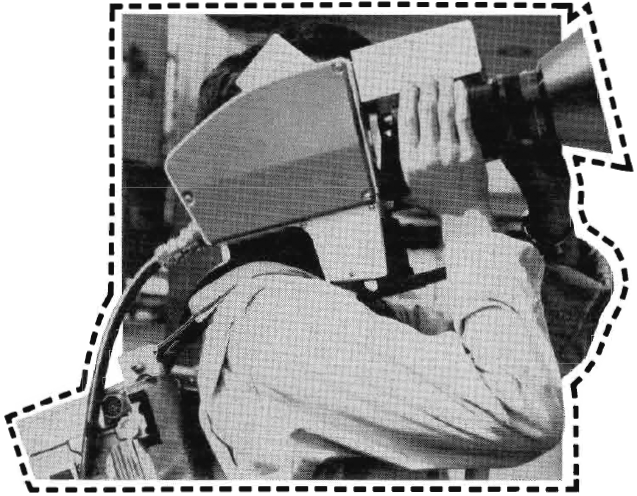

In 1975 the “fantastically lightweight” Ikegami HL-35 camera weighed 12 pounds — this was the camera head only. The backpack with the camera control unit was another 22 pounds.

If you wanted to record video in the field, you needed a portable tape recorder, which would be 31 pounds, not to mention an additional unit for A/C power and color playback.

By the end of the 1970s the equipment became smaller and lighter, but a camera and a recorder were still two separate units, connected with a cable.

No wonder that television news departments still used 16-mm film cameras whenever portability or ruggedness was required, not to mention image quality.

The difference between film, with fine details and cleanly delineated colors, and soft 3/4-inch video with horrendous color smearing was so noticeable, that many European broadcasters, in particular the BBC, continued to use film for factual programs well into the 1980s.

The cry for a film-style portable single-unit video camera was answered in 1981 with the development of a video recorder/camera (VRC), which:

- combined camera and recorder into one unit, getting rid of the umbilical cord between them;

- promised video quality better than 3/4-inch format;

- recorded on readily available and inexpensive consumer-grade tape.

Since the 1970s RCA experimented with analog component recording, which allowed to do away with a color subcarrier. This reduced moiré, color noise, and color streaks, usually associated with subcarrier processing in composite machines.

In 1981, RCA Broadcast Video Systems teamed up with Panasonic to produce a recording camera system for Electronic News Gathering (ENG) applications. Each company developed their own camera head but used the same recorder, officially described as a “joint development of Matsushita Electrical Industrial Co. Ltd. of Osaka, Japan and the RCA Corp.”

RCA pointed out that its “Hawkeye” camcorder “handled like a film camera.” According to the company, with no cables connecting camera to recorder, the operator had complete maneuverability.

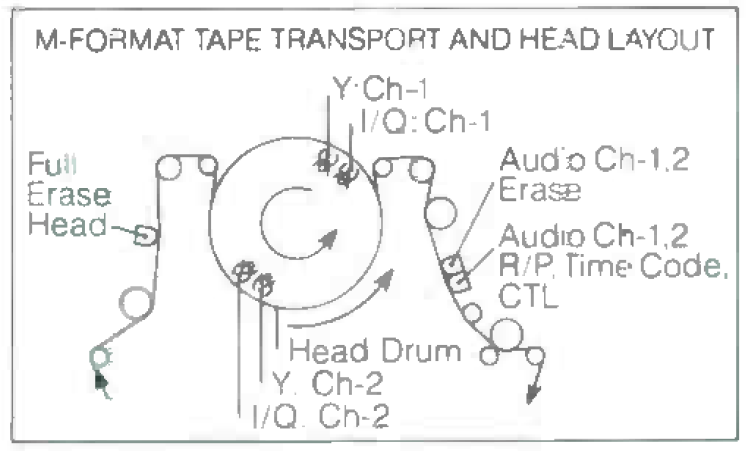

The recorder used standard VHS cassettes with the mechanism adapted from VHS tape recorder. Panasonic called its complete system “M-format”, alluding to the tape lacing method used on VHS machines; the Panasonic camcorder was named “Recam”.

RCA said the new recording format, which it called “ChromaTrak”, improved chrominance resolution, distortion, and noise by a factor better than 3:1 compared to 3/4 -inch cassette systems. Two audio tracks and a dedicated time code track were included.

The arrival of a combination color TV camera and recording unit had been predicted for some time as the next logical ENG development. It was generally assumed that the first such integrated camera/recorders would not arrive until a solid-state pickup array was ready. Therefore it came as a surprise at the 1981 NAB Convention to see not just one or two but four new combination camera/recorders not only from aforementioned RCA and Panasonic, but also from Sony, and from Nippon Television Company.

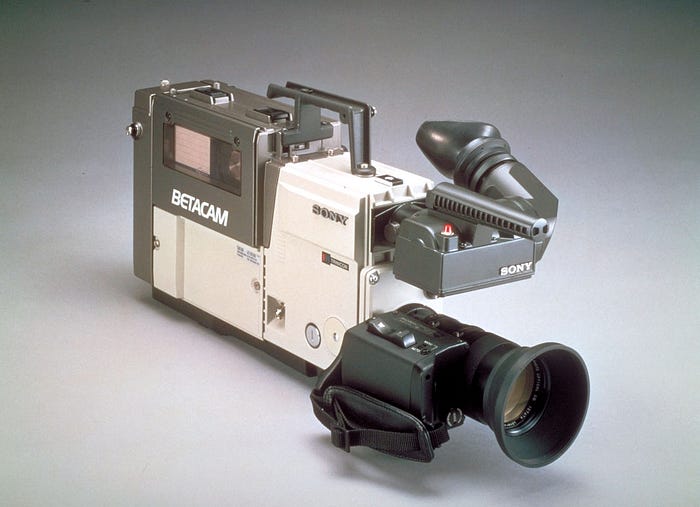

The Sony unit, which did not have official name at that time, but later was branded “Betacam”, was designed to use Betamax videocassettes as the recording medium and used a new highband Saticon Mixed Field (SMF) single tube branded as “Trinicon” with horizontal resolution of 400 TV lines. With just a single tube, the Sony camcorder weighed less than RCA and Panasonic camcorders.

Unlike the RCA, Panasonic and Sony products that used half-inch tape, the “CV-One” camcorder, developed for the Japanese NTV brodcasting company, recorded onto quarter-inch tape using the Funai Compact Video Cassette (CVC) format. The cassette was about the size of audio cassette.

Another difference is that the “CV-One” was a single-piece unit, while the RCA, Panasonic and Sony camcorders could be separated into camera head and recorder, and both components could be used independently.

Both RCA and Panasonic promised production units of their respective systems by the first quarter of 1982. The development was completed, and the two companies were ready to take orders. In fact, RCA started advertising its Hawkeye camcorder in the fall of 1981, promising deliveries “sooner than you think”.

Sony, on the other hand, anticipated to start marketing its system in Spring 1982.

The two new half-inch formats were in no way similar to those used in VHS or Betamax consumer products and they were not compatible with each other. Both systems offered 20 minutes of recording time from standard T120 VHS cassette (RCA/Panasonic) or L500 Betamax cassette (Sony).

It is peculiar that while RCA claimed in its white paper that it had developed a technique of time compression and time-division multiplexing, the RCA/Panasonic camcorder used frequency multiplexed components (the YIQ frequency-modulated signals). Sony Betacam, on the other hand, used time-multiplexed components (R-Y and B-Y signals) with compressed color.

In 1982 Bosch joined the emerging market of camcorders, presenting a pre-production version of a tape recorder/camera branded as Lineplex. Like the RCA, Panasonic and Sony units, it used component recording, with expanded luminance signal and compressed color signal, and it was also modular and could be split into camera head and recorder. Unlike those units, it used the CVC cassette with quarter-inch tape.

By 1982 Hitachi updated its single-piece SR-1 camcorder, developed under a research contract to Nippon Television, to a full professional-quality quarter-inch unit taking the analog component route with a luminance channel and a multiplexed I/Q channel.

Another Hitachi unit, the SR-10, used the half-inch “M”-format recorder.

The SR-1 was smaller than the Sony Betacam, so at one point Sony considered converting its consumer Betamovie single-piece camcorder into a professional one. This camcorder, BVW-2, was produced in limited quantities and handed to NHK, a Japanese broadcasting company.

At NHK’s news department, reporters were running the cameras, which is why small size and ease of operation was important. But the tube did not produce good enough image quality, so this camcorder was not sold outside of Japan.

In the summer of 1982 Betacam was not a complete system yet. Recam/Hawkeye, on the other hand, offered a complete set comprising camcorders, studio recorders and editing consoles, while third-party equipment manufacturers offered time base correctors and digital effects generators modified for the new system.

Early adopters rushed to purchase the Panasonic/RCA system, while the more cautious waited for Sony to start deliveries, to be able to compare the two formats and make an informed choice.

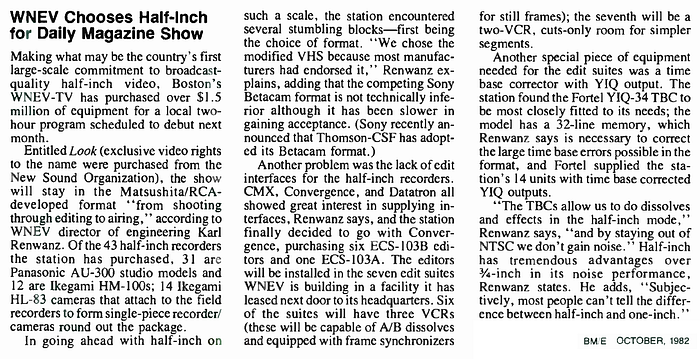

We evaluated M Format cameras and tape machines in June and July of 1982 and found the quality to be strikingly better than 3/4 -inch U -matic and subjectively difficult to tell from 1 -inch on many occasions.

The VHS videotape availability factor is favorable. However, we have found a need to use a super high grade VHS tape, because of excessive dropouts found in off-the-shelf VHS videotape. — Karl Renwanz, Director of Engineering WNEV-TV, Boston, MA

In October 1982, WKBD-TV 50, Detroit, purchased the RCA Hawkeye video recorder/camera system, becoming the first station in the world fully equipped in the new 1/2 -inch broadcast format. Their decision was based mainly because of the 3-tube camera, excellent videotape playback quality and equipment availability from stock.

They liked that the HCR-1 recording camera was completely self-contained and weighed 24.6 pounds, including camera, recorder, lens, view finder, microphone, cassette and battery. The 10.5 -pound camera head used three 1/2 -inch tubes.

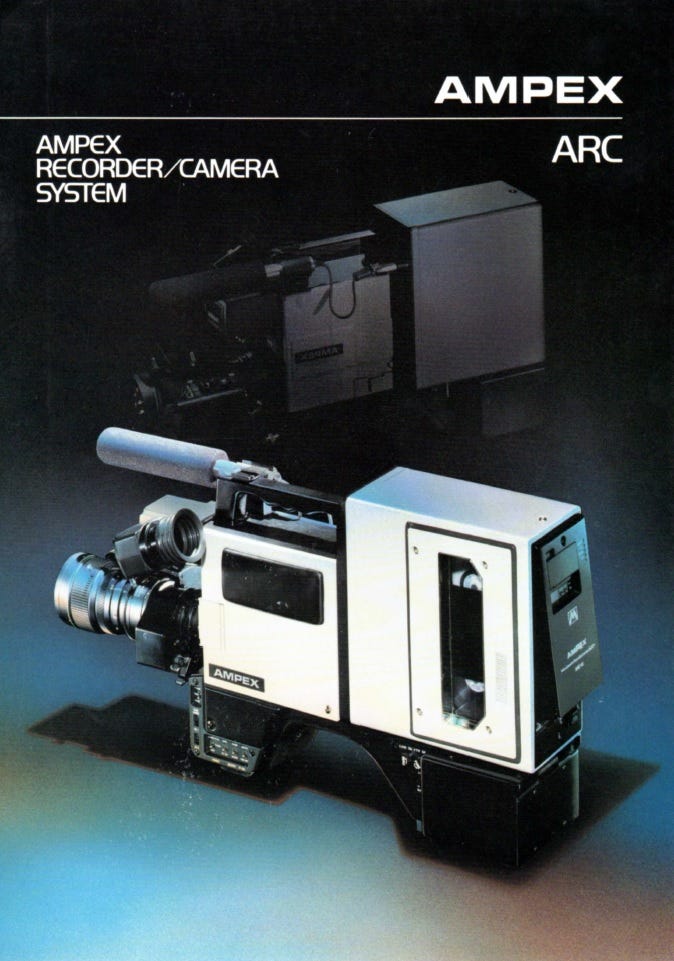

The same year, Ampex joined RCA/Panasonic alliance with a rebadged Panasonic Recam system christened ARC (Ampex Recorder/Camera).

Meanwhile, in the spring 1982 Sony started taking orders for its Betacam camcorder. The BVW-1 had just one tube with lower resolution that the competitors — 400 lines compared to 650 lines — but it was well matched to the recorder, which was limited to 300 lines.

The L500 Betamax cassette, loaded with 500 ft. of tape, ran 3 times the Beta I speed (or 6 times the Beta II speed) and was good for 20 minutes of video.

Unlike Panasonic and RCA, who chose YIQ color encoding format that closely matched NTSC broadcast television standard, Sony chose Y/R-Y/B-Y format, which was more “international” so to speak, and better matched a recently adopted standard for digital component video.

The numbers were better, too. Betacam’s luminance bandwidth was wider than Recam’s, which provided higher resolution. Signal to noise ratio was also slightly better.

By the end of 1982 Sony released a three-tube version of the Betacam camera head, BVP-3, which was fully interchangeable with the earlier three-stripe version, BVP-1. The complete camcorder was called BVW-3 and still was lighter and cheaper than the RCA/Panasonic offerings.

By the end of 1982 both Sony and RCA scored half-inch sales: Field Communications started ENG operations at four of its stations with RCA Hawkeye one-piece units, while Corinthian Broadcasting spent $5 million for complete conversion to Betacam for all its stations’ news and EFP.

In the same year, Thomson of France joined the Betacam camp.

1983 was the year of a fierce format war between Betacam and M-format.

Hitachi joined the Panasonic/RCA camp with the HM-100 recorder, which could be carried on a shoulder strap or mounted on-board for use as a one-piece system.

Ikegami launched the Unicam camera, that was capable of accepting both on-board VCR formats.

Philips announced that it would adopt the Bosch quarter-inch Lineplex recording format for a new ENG recording camera which will feature 2/3 -inch pickup tubes. The company promised a complete line of playback and editing equipment.

Meanwhile, the Bosch Quartercam KBF-1, which was shown previous year in prototype, was demonstrated as a production item, priced at $41,800. Added to the system were a studio recorder and a field editor.

Soon thereafter Bosch, Philips, and Hitachi Denshi, which had the other quarter-inch system, announced that they would fully support any working committee which might be formed by SMPTE to establish quarter-inch standards.

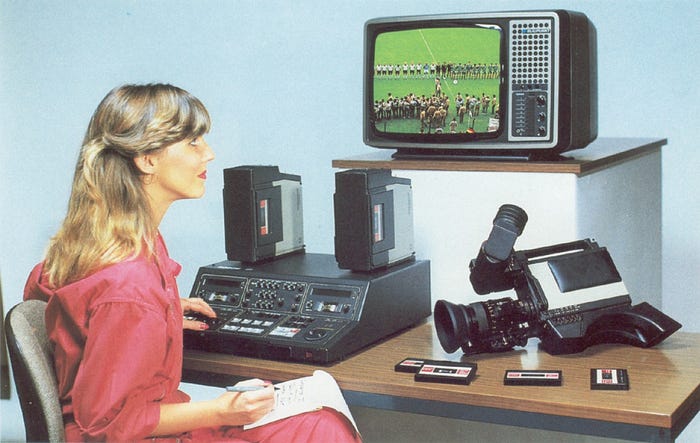

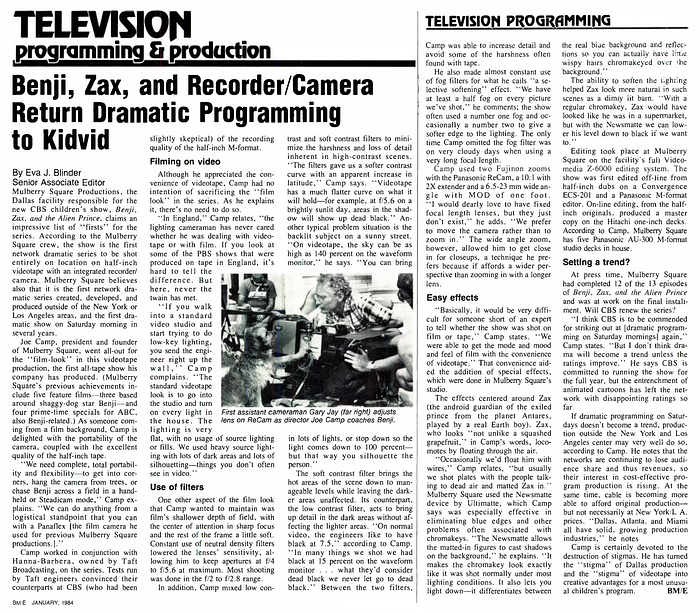

In 1983, Mulberry Square Productions created a new children’s show for CBS: Benji, Zax, and the Alien Prince. According to Mulberry Square, the show was the first network dramatic series to be shot entirely on location on half-inch videotape with an integrated recorder/camera. That recorder/camera was the Panasonic M-format camcorder.

The show was the first all-tape show for the company, who tried to achieve “film-look” using the available means, including cinematic lightning, shallower depth of field and soft contrast filter.

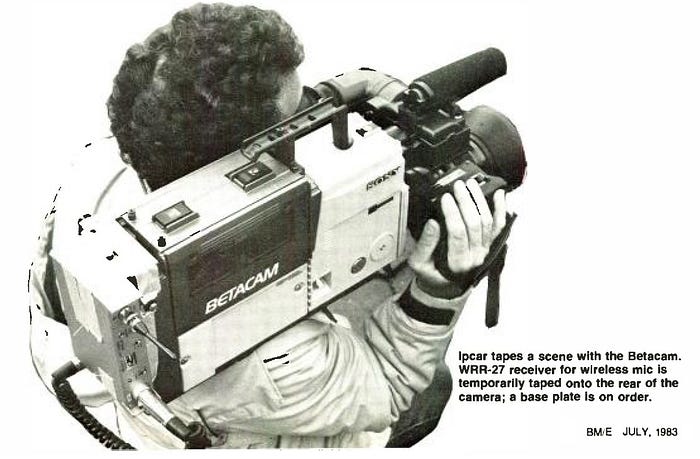

Capital Cities Television Productions used Sony’s Betacam half-inch video format for a documentary on adult illiteracy. Christopher Jeans, the producer, felt that the three-tube Betacam was a major advance over the M- format in quality. He also noted that large and cumbersome M-format camera did not record Dolbyized audio, lacked compatibility with film-style microphones and did not allow the operator [Bob Ipcar] to monitor sound while shooting.

By the end of 1983 more than 1,000 Betacams were sold to key end users, and Sony declared that Betacam had become the worldwide de facto standard.

In 1984 the Panasonic/RCA alliance shattered as RCA bailed out. Next year RCA closed its Broadcast Systems Division altogether.

Surprisingly, JVC, which was in close ties with Panasonic back then, did not embrace the M-format.

Meanwhile, CBS purchased of over $11 million worth of Sony Betacam equipment, committing itself to the new ENG format. The European Broadcasting Union adopted Betacam as its ENG format as well.

It became increasingly clear that Betacam had won the first round, so Panasonic rushed to redesign it system, and redesign it did.

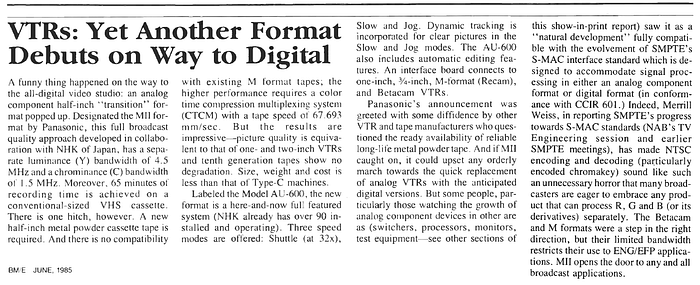

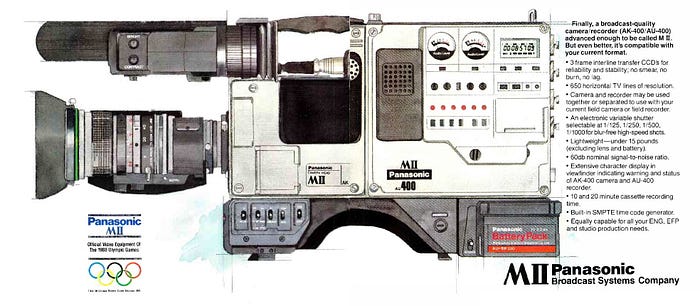

In 1985, Panasonic presented M-II, billed as a “transition format” on the way to the all-digital video studio. It had separate luminance bandwidth of 4.5 MHz and chrominance bandwidth of 1.5 MHz.

The YIQ format embodied in M-format was replaced with a (Y, R-Y, B-Y) system similar to Betacam. Using metal particle tape, M-II promised to offer quality comparable to that of one-inch systems.

The mechanism had been changed as well, the head drum was increased and M-type tape lacing was replaced with an approach similar to Sony’s U-load.

To reduce the recorder size, a smaller cassette was introduced. Loaded with thinner tape having metal coating — the technology that Fuji originally developed for 8-mm consumer video format — and helped with slower tape speed, the new cassette cassette stores 20 minutes of video — as much as the large VHS cassette in the older M-format.

The hubs of the small cassette are non-symmetric relative to the center of the cassette, this is because the studio VTR accepted both large and small cassettes, and the small one was inserted off-center.

The large cassette had been updated with metal tape as well, in can store store 90 minutes of video.

Increasing recording time was important, because broadcasters started using half-inch component video not only for ENG, but for producing longer-running programs. This was made evident by a stunning announcement by NBC that they had made a five-year, $50-million commitment to M-II.

NBC’s official announcement at 1986 NAB Convention said: “M-II is to be employed by all of the company’s operating divisions-NBC Television Network, NBC Television Stations, NBC News, NBC Sports, and NBC Operations and Technical Services- and it will be used at all levels-from news gathering in the field, to the 1988 Seoul Summer Olympics, to prime -time entertainment shows and commercial spots on all of NBC-TV.”

NBC found that the cost of supporting three principal formats (3/4 -inch, one -inch, and two-inch) was enormous and had approached all the major VTR manufacturers with its idea for a universal recorder. Only Panasonic MII response met their basic requirements.

Speculation on why things turned out the way they did was rampant at the convention. The most plausible of these scenarios held that NBC’s commitment to a “universal recording format” was inherently awkward for both Sony and Ampex, each of whom had a major share of the market for Type-C recorders. Sony also had a virtual lock on the 3/4-inch market in broadcast, and the adoption of a “universal recorder” would have required each of them to market against their own best and most successful products.

Moreover, both Ampex and Sony held valuable patents on technology associated with Type -C recording, and, in Sony’s case, valuable patents associated with U-matic recorders.

Matsushita, of course, with M -format a virtual washout, with no Type -C product, with a 3/4 -inch market in distant second, had few of the difficulties with a “universal recording concept” that its competitors have.

To bolster the new Panasonic’s format, JVC signed up with M-II.

But NBC contract was not enough to turn the tide in Panasonic’s favor. In 1986, Ampex, who previously marketed Panasonic’s Recam camcorder as Ampex ARC, defected from the Panasonic camp and signed a cross-licensing agreement with Sony. Sony got access to the Ampex digital composite video recording format, while Ampex has licensed Sony technology to manufacture and market Betacam camcorders and VTRs.

At that time, Betacam SP had not arrived yet, so Ampex was on the crossroads which it would begin manufacturing, standard Betacam or Betacam SP, but either way, the Sony/Ampex deal on Betacam technology made the Betacam format even more attractive. Another ally was Bosch, who dropped its Lineplex format and embraced Betacam.

According to Sony, about 25,000 Betacam systems have already been sold worldwide, with about 6000 sold in the U.S.

In 1987, NBC reaffirmed its reliance on M-II as the “universal format”, which had “met or exceeded” the network’s specifications for all of its videotape operations.

Panasonic launched a smaller camcorder with the camera head having three-chip CCD pickup with electronic shutter, and the recorder using the pocket-sized M-II cassette.

JVC showed its M-II equipment.

Sony launched Betacam SP, an updated and compatible variant of Betacam. SP machines could record both on conventional ferric oxide tape, as well as on new metal tape similar to one used in M-II machines.

Sony also introduced a large Betacam cassette, that could fit 60 or even 90 minutes of video, matching M-II.

For the ENG market, Sony launched the BVW-505 camcorder, which incorporated the BVV-5 Beta SP recorder. Ampex continued to reestablish itself in the camera market, manufacturing Beta SP equipment in the United States at the company’s Colorado Springs facility.

French Thomson-CSF licensed Betacam SP technology from Sony.

BTS, a joint Philips/Bosch company, showed its own line of Betacam equipment.

By 1989 Betacam SP established itself as the world’s most popular video acquisition format, supported by allies like Bosch, Philips, Thomson and Ampex.

BTS combined the recorder technology licensed from Sony with the camera side developed in-house. For example, the LDK 391 Betacam SP camcorder used the new FT-5 frame transfer chip having greater than 700-line resolution.

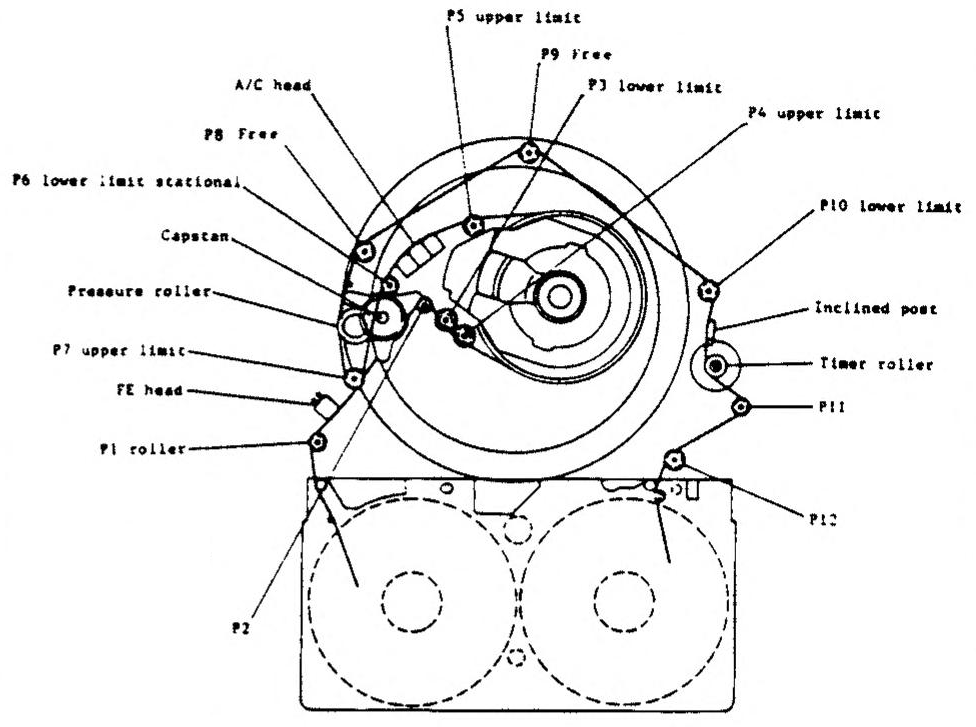

This single-piece camcorder, as well as its Sony sister models BVW-200/300/400, used a new compact mechanism. While Panasonic went from M-type loading on the M-format machines to something similar to U-type loading on the M-II increasing the size of the head drum in the process, Sony switched from its traditional U-type loading to a more compact scheme that resembled M-type loading.

The head drum size was reduced by 1/3, it was fitted with four heads instead of two, and the wraparound angle was increased from 180 to 270 degrees. Additionally, the cassette would move 15 mm towards the drum during loading, with the cassette shell partially overlapping the drum.

This allowed Sony to reduce camcorder size without developing a smaller cassette. Needless to say, this mechanism was fully compatible with existing Betacam and Betacam SP recordings.

Betacam, especially in its SP variant, proved to be a versatile format capable to replace old 2-inch studio dinosaurs, 3/4-inch ENG portapaks as well as 1-inch EFP machines. In the U.S., ABC and CBS moved hard news, then documentaries, then commercials, onto Betacam. NBC remained committed to M-II for news and commercials, and chose it as the official recording format for 1992 Olympic games.

By 1991, M-II was also employed by NHK in Japan, Thames TV in the United Kingdom, ORF in Austria and KBS in South Korea.

Everyone else used Betacam.

This victory of Betacam SP over MII was even more spectacular than the original Betacam vs M-format rivalry:

- Sony was partnered by Bosch, Philips, Thomson and Ampex, while Panasonic was joined only by JVC.

- Betacam and later Betacam SP became official ENG formats advised by EBU.

- Sony advertisement campaign was more efficient.

- Sony used a single name — Betacam — for all its component half-inch products, including the products marketed or even manufactured by Betacam licensees. Panasonic, and earlier, RCA and Ampex, used different names like M-format, M-Vision, Recam, Hawkeye, ColorTrak and ARC, which likely confused potential customers.

- Betacam SP machines could record and play both ferric oxide and metal tapes, ferric oxide tapes recorded in Betacam SP could be played on the original Betacam machines. On the contrary, M-II was not compatible with M, it was a completely new format.

- In terms of visual quality there was little difference between Betacam SP and MII recordings.

- Betacam SP tape was more robust, while thin MII and later D3 tape was found to be prone to oxidation. Track pitch on Betacam SP tape was twice wider than on MII tape, which improved reliability.

- By the end of 1980s, JVC and later Panasonic started advertising SVHS format to industrial and educational users and small broadcasters, leaving MII by the wayside and effectively admitting their defeat to Sony.

Component analog video became “bridge technology”, providing the pathway to higher-quality digital recording and playback. ■